DNA MAGAZINE

INTERVIEW

on DNA Magazine

Lucid dreams, auric fields and the journey to the subconscious in the works of Ana Montiel

Like an induction into a deep lucid dream of color and infinite possibilities, losing yourself in the works of Ana Montiel makes you feel a strong spiritual connection with the divinity of being that we find in each of us, an invitation to her mystical and empirical universe where science and spirituality flourish in the face of uncertainty, where Ana tries to take the pulse of life and understand her own existence.

More than a contemporary artist, Ana acts as a creative guide to the mapping of the unconscious, translating auric fields into canvas that manage to capture the intangibility of being and consciousness. Her works vibrate and resonate, a blurred matter before the eye that envelops you in a powerful sound that is only in your head, where the desire to evolve and not remaining still permeates everything.

In a time that has forced us to seclude ourselves inside to return to our center while opening an escape window to reality to spend more time dreaming, Ana has spent years experimenting with her dream time, training herself to access the oneiric world and be able to extract part of her inspiration from there, thus exploring different visual and ideological paths around the themes of metaphysics, phenomenology, consciousness and impermanence.

I’d like to begin asking your first memory of having contact with a work of art, do you remember what it was? where were you?

At home while I was growing up there were always windows into the arts… my parents were both art lovers although they didn't practice them professionally. My mother was a visual arts enthusiast and my father a pretty serious music lover. Looking back, I think that the visual artworks most engrained in my memory from my childhood years are by Pablo Picasso and Joan Miró.

Your works serve as a map to your subconscious, multicoloured universes that surround the viewer transporting them to a parallel reality, almost like the works of James Turrell. What emotions are the ones that serve as your main engine to create?

In my life and work I try to embrace the whole spectrum of emotions that come to the surface. Recognising both the lights and the shadows. For me, everything has its place and all is equally valuable. I also feel that the deeper we go within ourselves the easier it is to establish a connection with everything and everyone else. When we leave conditioning behind—the mask of our social personalities—and connect with our most human and timeless essence we all are very similar ... we all want to be happy, loved, etc. For me, both in my work and in my life, it is key to promote the unconditional acceptance of all the range of emotions so that I can have the most complete picture possible. I try not to filter or prioritise some impressions, ideas or emotions over other in a rational way. I let this process be as organic as possible, trying to respect the course of life and ideas.

Have you always been curious about the intersection of art and consciousness?

I have always had a clear interest in both of them but at first I did not link them in a direct way, at least consciously. I think that they started merging in a very organic way over the years... my personal and spiritual work showed me visual and ideological paths to explore with my art practice, and my practice makes me reflect on issues of metaphysics, phenomenology, consciousness, impermanence, etc.

What kind of visual or sensory references do you usually look for to inspire you?

I am very curious and always up to learn new things, see new things, make free association of ideas, etc. Inspiration can come out of anywhere, and I feel that it is essential to be very responsible and committed to the education that you promote for yourself. Never letting the mind, eye, body, or spirit stagnate. When I’m working on a project I try as much as possible not to have any clear references from other places in my conscious mind, but I imagine that I have a lot of them accumulated in my subconscious, which are manifesting in one way or another.

For years I have been paying close attention to my dreams, experimenting with nootropics, and training myself to have lucid dreams as often as I can ... the oneiric realm is an incredibly fertile ground for me, and many ideas and associations come out of it. While I sleep, I always have something to write down or record by my side, and I often wake up in the middle of the night to jot down ideas and reflections that have arisen within a dream.

If your works had a sound or soundtrack, what would it be?

Sometimes I make playlists including music that I feel belong to the same realm than a particular group of artworks. Like this one I made for Fields, this one that I did for “Polyphonies of Perception” (the solo show I had last year at joségarcía ,mx in Mexico City, or this one I made recently for “Us as a Poem of Delusion” (a set of artworks I made for UCCA Dune -China- that is part of their “Resistance of the Sleepers” exhibition).

There is a certain degree of spirituality and peace that causes me to see the mixture of colours in your pieces. How are your beliefs and concerns for the future reflected in your art?

I try to be as honest and transparent as I can, both in my personal life and in my art practise. I believe that what worries, excites, hurts or intrigues me permeates my work in one way or another.

Even with the pandemic triggering economic collapse, there has been pressure in recent months to stay productive. How did you manage to maintain your peace of mind during these last weeks at home? And did you find any new way to stay creative even in the running of the bulls?

We live in a society badly damaged by ideologies tied to productivity and material gain... capitalist and neoliberal doctrines are so ingrained into the system that in order to free ourselves from them we would need a period of intensive unlearning... reviewing structures, dreaming new dreams, devising new formulas that we could implement, etc. In my opinion this is a very critical moment, I personally feel that it is much larger and way more complex than what we can perceive. I believe it is the beginning of a transition… and that this first stage is focused on the crumbling and the overall crisis of the obsolete paradigms on which the current system is based.

For me personally the quarantine has been a silent retreat of sorts, in which I have reflected a lot on the global situation and therefore on an emotional level it has been a bit of a roller coaster... Some issues have made me very sad and the situation has frustrated me in many fronts. It’s been very helpful to do practise meditation more than usual, also to practise qigong, do some gardening, cooking, reading, drawing and painting... I have to confess I am a workaholic, I spend most of my time concentrated on work, and in this situation, sometimes I felt that I was not being as productive as I would have liked—although I feel that I have come a long way in terms of ideas. On an emotional level I worked hard on developing more compassion towards myself when I am not as productive or positive as I would have liked. Trying to allow myself to be fully present in all situations—even in uncomfortable ones—to understand and integrate them without censoring or limiting them. I think that despite the frustration that this global situation entails, it must be recognised as a very valuable exercise of patience.

At home while I was growing up there were always windows into the arts… my parents were both art lovers although they didn't practice them professionally. My mother was a visual arts enthusiast and my father a pretty serious music lover. Looking back, I think that the visual artworks most engrained in my memory from my childhood years are by Pablo Picasso and Joan Miró.

Your works serve as a map to your subconscious, multicoloured universes that surround the viewer transporting them to a parallel reality, almost like the works of James Turrell. What emotions are the ones that serve as your main engine to create?

In my life and work I try to embrace the whole spectrum of emotions that come to the surface. Recognising both the lights and the shadows. For me, everything has its place and all is equally valuable. I also feel that the deeper we go within ourselves the easier it is to establish a connection with everything and everyone else. When we leave conditioning behind—the mask of our social personalities—and connect with our most human and timeless essence we all are very similar ... we all want to be happy, loved, etc. For me, both in my work and in my life, it is key to promote the unconditional acceptance of all the range of emotions so that I can have the most complete picture possible. I try not to filter or prioritise some impressions, ideas or emotions over other in a rational way. I let this process be as organic as possible, trying to respect the course of life and ideas.

Have you always been curious about the intersection of art and consciousness?

I have always had a clear interest in both of them but at first I did not link them in a direct way, at least consciously. I think that they started merging in a very organic way over the years... my personal and spiritual work showed me visual and ideological paths to explore with my art practice, and my practice makes me reflect on issues of metaphysics, phenomenology, consciousness, impermanence, etc.

What kind of visual or sensory references do you usually look for to inspire you?

I am very curious and always up to learn new things, see new things, make free association of ideas, etc. Inspiration can come out of anywhere, and I feel that it is essential to be very responsible and committed to the education that you promote for yourself. Never letting the mind, eye, body, or spirit stagnate. When I’m working on a project I try as much as possible not to have any clear references from other places in my conscious mind, but I imagine that I have a lot of them accumulated in my subconscious, which are manifesting in one way or another.

For years I have been paying close attention to my dreams, experimenting with nootropics, and training myself to have lucid dreams as often as I can ... the oneiric realm is an incredibly fertile ground for me, and many ideas and associations come out of it. While I sleep, I always have something to write down or record by my side, and I often wake up in the middle of the night to jot down ideas and reflections that have arisen within a dream.

If your works had a sound or soundtrack, what would it be?

Sometimes I make playlists including music that I feel belong to the same realm than a particular group of artworks. Like this one I made for Fields, this one that I did for “Polyphonies of Perception” (the solo show I had last year at joségarcía ,mx in Mexico City, or this one I made recently for “Us as a Poem of Delusion” (a set of artworks I made for UCCA Dune -China- that is part of their “Resistance of the Sleepers” exhibition).

There is a certain degree of spirituality and peace that causes me to see the mixture of colours in your pieces. How are your beliefs and concerns for the future reflected in your art?

I try to be as honest and transparent as I can, both in my personal life and in my art practise. I believe that what worries, excites, hurts or intrigues me permeates my work in one way or another.

Even with the pandemic triggering economic collapse, there has been pressure in recent months to stay productive. How did you manage to maintain your peace of mind during these last weeks at home? And did you find any new way to stay creative even in the running of the bulls?

We live in a society badly damaged by ideologies tied to productivity and material gain... capitalist and neoliberal doctrines are so ingrained into the system that in order to free ourselves from them we would need a period of intensive unlearning... reviewing structures, dreaming new dreams, devising new formulas that we could implement, etc. In my opinion this is a very critical moment, I personally feel that it is much larger and way more complex than what we can perceive. I believe it is the beginning of a transition… and that this first stage is focused on the crumbling and the overall crisis of the obsolete paradigms on which the current system is based.

For me personally the quarantine has been a silent retreat of sorts, in which I have reflected a lot on the global situation and therefore on an emotional level it has been a bit of a roller coaster... Some issues have made me very sad and the situation has frustrated me in many fronts. It’s been very helpful to do practise meditation more than usual, also to practise qigong, do some gardening, cooking, reading, drawing and painting... I have to confess I am a workaholic, I spend most of my time concentrated on work, and in this situation, sometimes I felt that I was not being as productive as I would have liked—although I feel that I have come a long way in terms of ideas. On an emotional level I worked hard on developing more compassion towards myself when I am not as productive or positive as I would have liked. Trying to allow myself to be fully present in all situations—even in uncomfortable ones—to understand and integrate them without censoring or limiting them. I think that despite the frustration that this global situation entails, it must be recognised as a very valuable exercise of patience.

In addition to experimenting with different states of consciousness, what other themes serve as inspiration?

I am passionate about trying to take the pulse of life, trying to understand our existence. I think that both my work and my life could be reduced to that. I spend my time trying to perceive patterns with which to glimpse an order that I have not perceived before, trying to understand the function of consciousness, making peace with impermanence and the uncertainty of everything...

Exploring different states of consciousness is more like a tool to observe from different perspectives, it helps me detach myself from rigid mental structures.

What role does neuroscience and quantum physics play in your works?

They make sense and put into words more abstract ideas and empirical impressions. In my opinion there is a direct correlation between spiritual exploration and scientific exploration. I feel that both science and spirituality thrive in the face of uncertainty, and that attracts me immensely. I love the exchanges of ideas between scientist David Bohm and Jiddu Krishnamurti, books like "Waking, Dreaming, Being: Self and Consciousness in Neuroscience, Meditation, and Philosophy" by Evan Thompson or "The Quantum and The Lotus ”by Matthieu Ricard and Trinh Thuan.

What influence has Mexican culture had on your creative process?

The way things move forward in such an organic way here in Mexico has definitely encouraged my practice and process to flow and evolve more effortlessly. The shamanic work and the spiritual search that I have delved into during my years in Mexico have also been key to my work.

We have seen how for several seasons already, how many designers and artists use post apocalyptic and futuristic references for their works and creations. Some artists work through chaos with more chaos and others respond by imagining new worlds. Have you thought about utopias or dystopias during your creative process in recent months?

I think of both utopias and dystopias often, but I try not to include the various hypotheses, conjectures and neuroses of my mind into my creative process. This may sound a bit newagey, but for the process with my work I try to put myself at the service of something greater, I try to enter a more transpersonal/timeless mode, with respect and humility.

I consider dreaming and planning utopias a very important thing—as well as recognising dystopias in order to avoid them—but for the moment I am not incorporating intentionally any of this into my work, but into my personal life. Optimising my way of life, making future plans, etc…

Do you think that art should reflect the times we live in or challenge and shape them?

I believe that art has many subdivisions and functions, and that each artist or human being chooses their battles or themes in which to focus. I personally aspire to something not too tied to a defined moment or place with my work, but it seems very important to me that there are people who actively interact with the present moment through their artistic work. I put into practice that interaction and that "taking the pulse of the times" attitude in my personal life… for example, I can be a very political person in a conversation, or when making choices in my daily life, but I try not to include all that in my artwork.

Can art change the course of the future?

More than art I would say that humans can change the course of the future ... whether they practice art or not. I feel that it is unfair to put pressure on the disciplines, after all they are tools, and the ideas and attitudes of those who use those tools are the responsible part of the equation. Everything is possible, and I think it is important that we all recognise the importance that our actions, intentions and reactions can have ... each person has different sets of tools and they all are valuable!

What gives you hope?

Those moments in which life puts you in your place and you recognise your scale. What a tiny and insignificant piece you are in such a huge and complex puzzle. Moments in which I can transcend my limited perception of reality give me both hope and peace.

It also gives me hope not understanding so many things. I feel that it challenges me to keep trying to learn, understand, question... and it also reminds me of my place regarding the whole (which is again pretty insignificant).

I am passionate about trying to take the pulse of life, trying to understand our existence. I think that both my work and my life could be reduced to that. I spend my time trying to perceive patterns with which to glimpse an order that I have not perceived before, trying to understand the function of consciousness, making peace with impermanence and the uncertainty of everything...

Exploring different states of consciousness is more like a tool to observe from different perspectives, it helps me detach myself from rigid mental structures.

What role does neuroscience and quantum physics play in your works?

They make sense and put into words more abstract ideas and empirical impressions. In my opinion there is a direct correlation between spiritual exploration and scientific exploration. I feel that both science and spirituality thrive in the face of uncertainty, and that attracts me immensely. I love the exchanges of ideas between scientist David Bohm and Jiddu Krishnamurti, books like "Waking, Dreaming, Being: Self and Consciousness in Neuroscience, Meditation, and Philosophy" by Evan Thompson or "The Quantum and The Lotus ”by Matthieu Ricard and Trinh Thuan.

What influence has Mexican culture had on your creative process?

The way things move forward in such an organic way here in Mexico has definitely encouraged my practice and process to flow and evolve more effortlessly. The shamanic work and the spiritual search that I have delved into during my years in Mexico have also been key to my work.

We have seen how for several seasons already, how many designers and artists use post apocalyptic and futuristic references for their works and creations. Some artists work through chaos with more chaos and others respond by imagining new worlds. Have you thought about utopias or dystopias during your creative process in recent months?

I think of both utopias and dystopias often, but I try not to include the various hypotheses, conjectures and neuroses of my mind into my creative process. This may sound a bit newagey, but for the process with my work I try to put myself at the service of something greater, I try to enter a more transpersonal/timeless mode, with respect and humility.

I consider dreaming and planning utopias a very important thing—as well as recognising dystopias in order to avoid them—but for the moment I am not incorporating intentionally any of this into my work, but into my personal life. Optimising my way of life, making future plans, etc…

Do you think that art should reflect the times we live in or challenge and shape them?

I believe that art has many subdivisions and functions, and that each artist or human being chooses their battles or themes in which to focus. I personally aspire to something not too tied to a defined moment or place with my work, but it seems very important to me that there are people who actively interact with the present moment through their artistic work. I put into practice that interaction and that "taking the pulse of the times" attitude in my personal life… for example, I can be a very political person in a conversation, or when making choices in my daily life, but I try not to include all that in my artwork.

Can art change the course of the future?

More than art I would say that humans can change the course of the future ... whether they practice art or not. I feel that it is unfair to put pressure on the disciplines, after all they are tools, and the ideas and attitudes of those who use those tools are the responsible part of the equation. Everything is possible, and I think it is important that we all recognise the importance that our actions, intentions and reactions can have ... each person has different sets of tools and they all are valuable!

What gives you hope?

Those moments in which life puts you in your place and you recognise your scale. What a tiny and insignificant piece you are in such a huge and complex puzzle. Moments in which I can transcend my limited perception of reality give me both hope and peace.

It also gives me hope not understanding so many things. I feel that it challenges me to keep trying to learn, understand, question... and it also reminds me of my place regarding the whole (which is again pretty insignificant).

VOGUE magazine

(MX)

I perceive this moment as an involuntary initiation, longer and way more complex than we can perceive. At this time, I feel that it is key to stay connected to the feeling of humility that comes hand in hand with situations of uncertainty... it’s important not to take anything for granted and to stay open to changes, from a mindframe rooted in empathy and common sense”

Ana Montiel

Ana Montiel

Interview

transcript from Umbigo Magazine (PT)Josseline Black – In this phase of forced isolation, how are you articulating your response in a public discourse? What is your role in this larger conversation?

Ana Montiel – I’m not articulating any response in an intentional way and I think it’s not my place to say what’s my role; I just do what feels right. I think that the key during these uncertain times (and always for that matter) is to be as honest, open, and as human as possible. To feel empathy while maintaining an attitude of discernment. To keep our minds as balanced as we can, and our hearts open.

JB – Has your artistic practice changed through isolation?

AM – This temporary isolation is definitely making me deepen my practice. Less distractions and much food for thought.

JB – How has your practical capacity to produce work been affected by the pandemic?

AM – Some artworks and projects that involved other people in the production are on hold for obvious reasons, but the pieces that I do by myself are moving full speed ahead. I moved to this new place last February, it’s a big house in Mexico City that has plenty of different areas that serve for diverse purposes. So far, it’s being very fluid working from here.

JB – What is your approach to collaboration at the moment?

AM – I’m always open to collaborate and exchange ideas.

JB – How would you define the present moment, metaphysically/literally/symbolically?

AM – I see it as a global rite of passage, as some sort of initiation that we need to face with an attitude of openness and a positive mindset in order to reformulate obsolete paradigms and build better and stronger structures for the future. This situation is bringing up our shadows for us to face them, all this can seem overwhelming at times but growth doesn’t happen within comfort.

JB – Do you see the potential for renewed support for cultural production in spite of macro and micro-economies which are currently rapidly restructuring?

AM – Every country is a different story… some regions support the arts more seriously than others. No idea how the current situation is going to impact, to be honest, these are unprecedented times and my opinion would be a mere conjecture… I’ve been living in Mexico for almost six years now; before I used to live in London. When I relocated here, I was a bit shocked at the lack of support from the government—not only towards the arts but with many other things. I feel that this, however, has a bright side as it creates a great resilience among the people and an amazing flexibility to surf the waves amidst crisis and uncertainty. What I see as key in all this process is to not try to replicate old systems but strive to find new ones. This pause is giving us time to think, and maybe some innovative ideas come up to plant better seeds for the future!

Ana Montiel – I’m not articulating any response in an intentional way and I think it’s not my place to say what’s my role; I just do what feels right. I think that the key during these uncertain times (and always for that matter) is to be as honest, open, and as human as possible. To feel empathy while maintaining an attitude of discernment. To keep our minds as balanced as we can, and our hearts open.

JB – Has your artistic practice changed through isolation?

AM – This temporary isolation is definitely making me deepen my practice. Less distractions and much food for thought.

JB – How has your practical capacity to produce work been affected by the pandemic?

AM – Some artworks and projects that involved other people in the production are on hold for obvious reasons, but the pieces that I do by myself are moving full speed ahead. I moved to this new place last February, it’s a big house in Mexico City that has plenty of different areas that serve for diverse purposes. So far, it’s being very fluid working from here.

JB – What is your approach to collaboration at the moment?

AM – I’m always open to collaborate and exchange ideas.

JB – How would you define the present moment, metaphysically/literally/symbolically?

AM – I see it as a global rite of passage, as some sort of initiation that we need to face with an attitude of openness and a positive mindset in order to reformulate obsolete paradigms and build better and stronger structures for the future. This situation is bringing up our shadows for us to face them, all this can seem overwhelming at times but growth doesn’t happen within comfort.

JB – Do you see the potential for renewed support for cultural production in spite of macro and micro-economies which are currently rapidly restructuring?

AM – Every country is a different story… some regions support the arts more seriously than others. No idea how the current situation is going to impact, to be honest, these are unprecedented times and my opinion would be a mere conjecture… I’ve been living in Mexico for almost six years now; before I used to live in London. When I relocated here, I was a bit shocked at the lack of support from the government—not only towards the arts but with many other things. I feel that this, however, has a bright side as it creates a great resilience among the people and an amazing flexibility to surf the waves amidst crisis and uncertainty. What I see as key in all this process is to not try to replicate old systems but strive to find new ones. This pause is giving us time to think, and maybe some innovative ideas come up to plant better seeds for the future!

JB – E.M Cioran writes: “in major perplexities, try to live as history were done with and to react like a monster riddled by serenity”, how do you respond to this proposal?

AM – It’s important to stay open to the new without forgetting the past, so that it can remind us not to make mistakes from before. We need to be humble and take responsibility for our actions. Own our words, walk our talk. Be empathetic and consider as many points of view as possible… in short, inviting equanimity to the party as much as we can!

JB – How is this time influencing your perception of alterity in general?

AM – I reflect a lot on the idea of alterity… lately even more as I’m practising meditation more than usual during the quarantine. This might sound a bit out there, but transcending the self in order to blend and merge is a very recurrent thought for me. I feel that if we would be able to blur the lines around the idea of “self” and experience oneness more often the world would be a kinder, more empathetic place.

JB – How is your utilisation of technology and virtuality evolving the paradigm within which you produce work?

AM – Personally, the more I use technology and have a virtual life, the more I crave (and look for) real intimacy and to experience a rich sensorial experience of my environment. I need that balance both in my work and in my life.

JB – What is your position on the relationship between catastrophe and solidarity?

AM – This is a delicate subject… In the face of a crisis, we humans turn to solidarity more easily. We become “more human” and our priorities seem to be clearer than before… we are all united against “something”… but what happens when the “external evil” is over? Does our humanness stay or do we stray amidst our busy self-centred lives? I have faith in humanity, but I feel there’s much work to do on us as a collective and to get to that point we need to do personal work each of us individually. Luckily this time of deceleration and self-reflection is a great opportunity for that ;)

* you can read the portuguese version of the interview here.

AM – It’s important to stay open to the new without forgetting the past, so that it can remind us not to make mistakes from before. We need to be humble and take responsibility for our actions. Own our words, walk our talk. Be empathetic and consider as many points of view as possible… in short, inviting equanimity to the party as much as we can!

JB – How is this time influencing your perception of alterity in general?

AM – I reflect a lot on the idea of alterity… lately even more as I’m practising meditation more than usual during the quarantine. This might sound a bit out there, but transcending the self in order to blend and merge is a very recurrent thought for me. I feel that if we would be able to blur the lines around the idea of “self” and experience oneness more often the world would be a kinder, more empathetic place.

JB – How is your utilisation of technology and virtuality evolving the paradigm within which you produce work?

AM – Personally, the more I use technology and have a virtual life, the more I crave (and look for) real intimacy and to experience a rich sensorial experience of my environment. I need that balance both in my work and in my life.

JB – What is your position on the relationship between catastrophe and solidarity?

AM – This is a delicate subject… In the face of a crisis, we humans turn to solidarity more easily. We become “more human” and our priorities seem to be clearer than before… we are all united against “something”… but what happens when the “external evil” is over? Does our humanness stay or do we stray amidst our busy self-centred lives? I have faith in humanity, but I feel there’s much work to do on us as a collective and to get to that point we need to do personal work each of us individually. Luckily this time of deceleration and self-reflection is a great opportunity for that ;)

* you can read the portuguese version of the interview here.

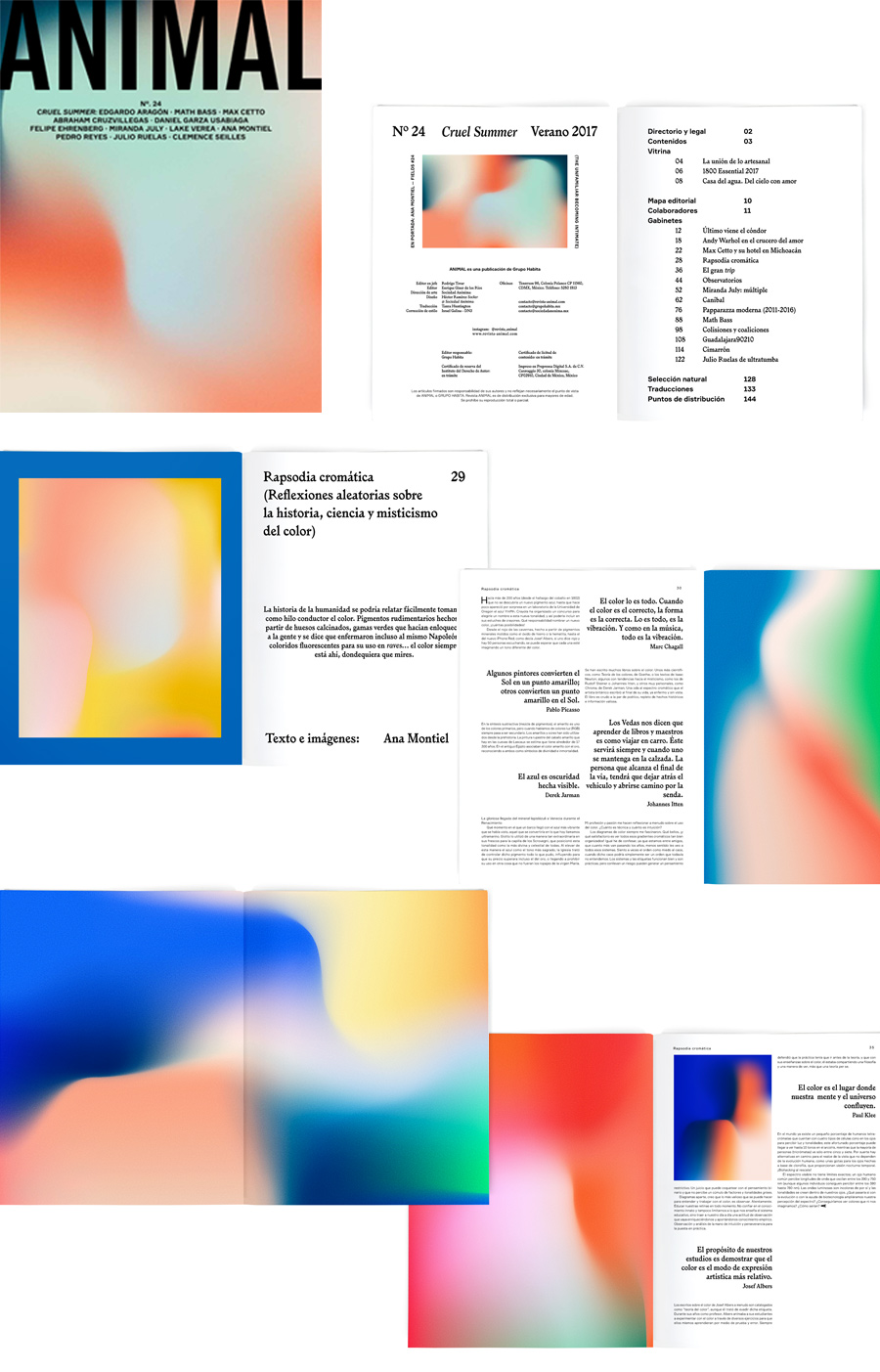

Polyphonic Fields

at The Steidz magazine

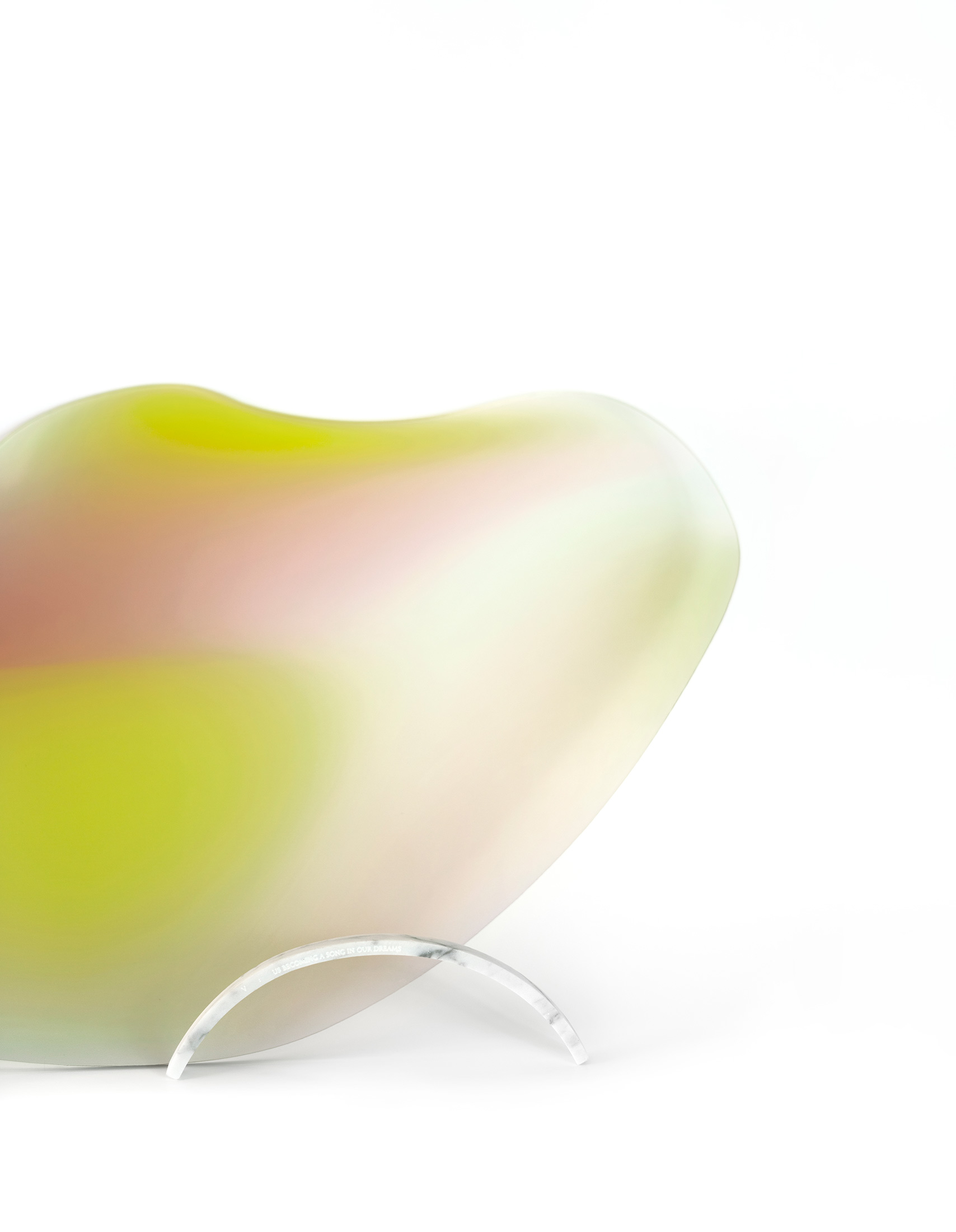

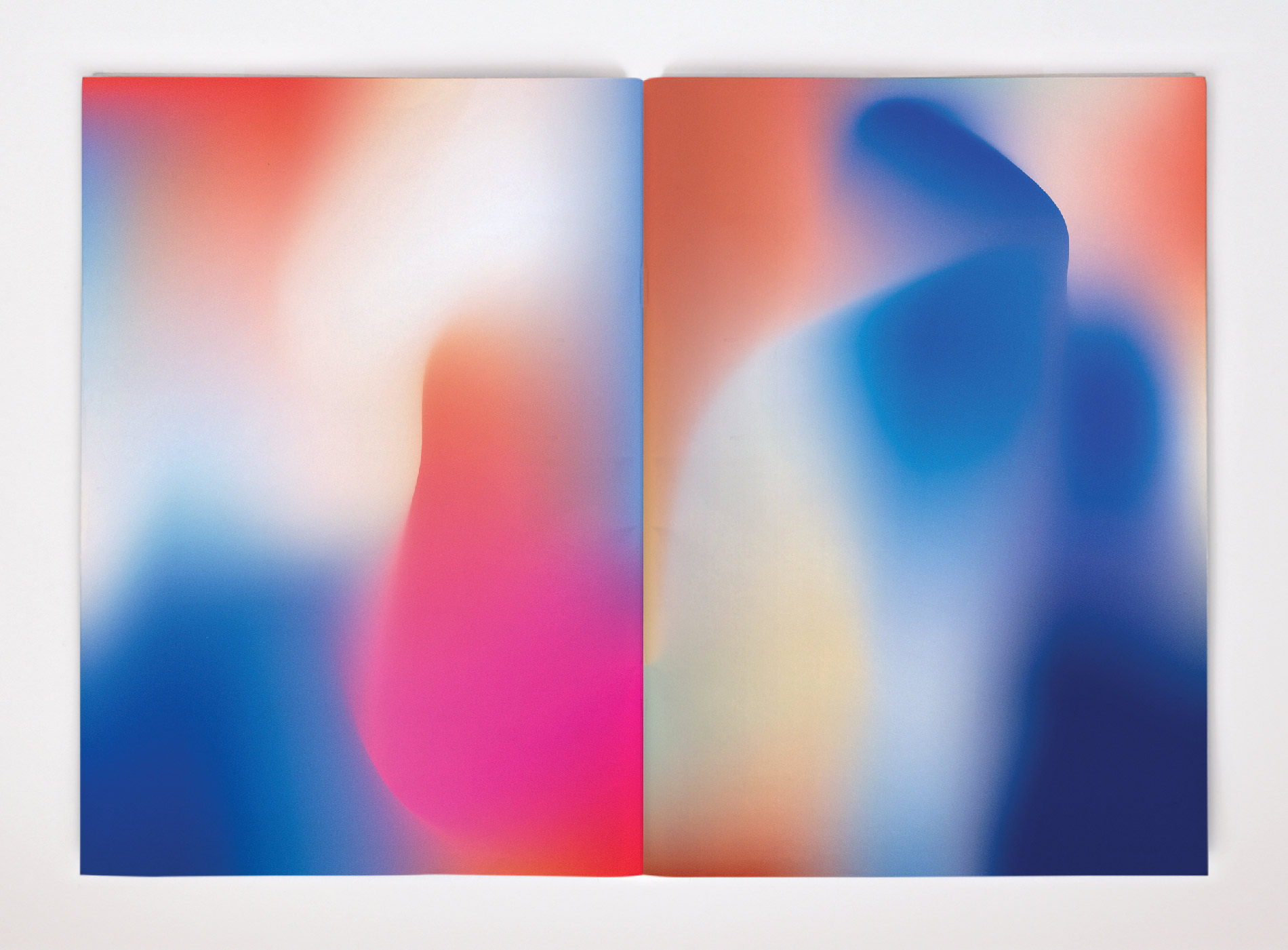

Taking in her paintings is like opening your eyes after a nap in the sand. The colourful masses on her canvas appear to be in motion, plunging the spectator into a semi-conscious state. Beyond the merely pictorial, Ana Montiel's works read like spiritual, dreamlike invitations, that hit you with a feeling of satisfaction and involuntary entrancement.

Any tangible form looks acid-washed; a silhouette or a ray of sun gives way to a sfumato of light and pigments. The artist is interested in the conceptual issues of perception and phenomenology, based on the premise that reality is nothing but a collective and controlled hallucination. Intrigued by neuroscience and quantum physics, she considers herself a "mapper of the unconscious", producing the Fields series -a multicoloured adventure meant as a tribute to the intangible.

In the course of practicing hybrid art, drifting from drawing to design to artistic direction, Ana Montiel shunned painting during her school years before finally embracing it. Originally from Spain (b. 1981), the artist worked in Barcelona and then in London, before settling down in Mexico. Her colour palette stimulates both visually and acoustically, like a kind of chorus, giving each spectator their own unique symphony. Ana Montiel's art vibrates, resonates, and performs a kind of synaesthesia, marrying noise and matter, pixel and sound. Indeed, before setting to work, the artist communes with her canvas thanks to a moment of musical and physical awakening. She gathers the colours and applies them carefully with her spray gun. The tints fuse, superimpose, then come to rest. Deatail by detail, each grain of colour is adjusted according to a meticulous method of application of acrylics, with some paintings having up to forty sub-layers. The effect is magnetic, in much the same vein as the mystical installations of American artist James Turrell or the meditative velvets of the Italian Ettore Spaletti. With her pictorial works, Ana Montiel opens windows onto a world that topples us and shoves us towards new prophetic dimensions, dimensions of the infinite and unknown.

Text by Clélia Dehon -

Head of Public Program at Louis Vuitton Foundation

THIS HUMAN EXPERIENCE WE SHARE

(THESE DAYS OF FICTION)

A tidal lock showing us only our own version of reality. Us and our experience candidly gazing at each other, we can only see our faces, our backs will always remain unseen. This is a phenomenological orbit behaving as a mechanical choreography.

We are in a constant altered state of consciousness… but which state is not altered consciousness?

Perception untamed — distorted and subjective in its depths, while sensible and thorough in its surface. An involuntary irreality, automatic. We are in a romance with the opaque in this shared fiction that brings us together.

Ana Montiel, 2019

ESTA EXPERIENCIA HUMANA QUE COMPARTIMOS

(ESTOS TIEMPOS DE FICCIÓN)

Una rotación sincrónica que solo nos muestra una versión de las cosas. Nosotros y nuestras experiencias con miradas fijas entrelazadas, solo nos miramos a los ojos, nunca nos veremos las espaldas. Esta es una órbita fenomenológica a modo de danza automática.

Un estado alterado de conciencia constante... ¿pero qué estado no es conciencia alterada?

Percepción indómita; distorsionada y subjetiva en su fondo, cabal y acertada en su superficie. Una irrealidad involuntaria, automática. Vivimos en un romance con lo opaco, en esta ficción colectiva que nos une.

Un estado alterado de conciencia constante... ¿pero qué estado no es conciencia alterada?

Percepción indómita; distorsionada y subjetiva en su fondo, cabal y acertada en su superficie. Una irrealidad involuntaria, automática. Vivimos en un romance con lo opaco, en esta ficción colectiva que nos une.

Questions about the nature of perception — the what, why, and how of consciousness — have been driving the work of Mexico-based artist Ana Montiel lately. And while any definitive answers to such age-old puzzles remain elusive, Montiel’s work provides a kind of aesthetic response, making those mysteries both visual and material. There’s a mesmeric, meditative quality to her canvas and digitally-created color field paintings, reminiscent of the Light & Space art of the ’60s and ’70s. Something quietly active occurs while viewing them, though the works themselves are static; engaging with her pieces and the ideas behind them can encourage a kind of headiness, but her work is also just a pleasure to look at.

In the last few years, Montiel has shown internationally at galleries, as she’s moved around the world herself. Montiel was born and raised in Logroño, Spain. Pursuing her BFA brought her to the University of Barcelona, and she stayed in that city for over a decade before moving to London. After five years there, a visit to Mexico City convinced her that’s where she wanted to be. “When I got back to London, I gave away around 95 percent of my stuff and moved, with just two suitcases and my elderly cat.” It’s been a productive, generative shift for Montiel. For over three years now, she’s made her home in Tepoztlan, a village about an hour outside of Mexico City. “The rural pace tames my hyperactive mind and lets me concentrate on my practice.”

The intensity and commitment she brings to her artistic process — from reading in-depth about quantum physics and neuroscience to experimenting with altered states — is visible in what she creates but it’s also balanced by a lightness and ethereality. We recently got in touch with her via email to learn more.

Can you tell us about your process?

When I paint, I try to first get into a state of concentration, some sort of trance. I get there through music, Kundalini, breath work or something along those lines (my painting doesn’t work well if my state of mind is the one I have when I do my taxes or reply to e-mails).

I start mixing a few colors, then I apply them with a spray gun. I examine the paintings carefully, continue mixing new hues that I feel could work well and continue layering new colors until I feel I need to let the paintings rest. Some of them have around 15 layers of color but others may have up to 40! It’s a gamble, I always want to add a bit more detail to enrich the colored grain but each application carries a risk of ruining the whole thing.

I actually would love to spend more time painting but all the ideas in the background take more time than the actual paintings, at least that’s what’s happened until now. Each project asks for something different: I spend my days reading, thinking, writing, and testing things. This constant flux of ideas influences directly my practice in different ways. I also try to make my subconscious mind an active collaborator in my practice in different ways. Very often I wake up from my dreams to write down ideas for pieces, projects, sentences, titles, etc.

During my student years I was more passionate about sculpture, installation and photography than about drawing or painting. There were so many students focused on channeling the archetype of the sacrosanct painter that I got a bit turned off by the idea of it. My impression at that time was that it had too much to do with feeding the ego of the character you were creating. It wasn’t until many years later that I found a way to get closer to painting, believing that this medium can be as selfless and ethereal as it is for me now.

To what extent is your work created physically vs. digitally?

I embrace both the digital work and the so-called physical one. After reading so much about quantum physics and that what we perceive as solid I decided not to make distinctions with my artwork and its mediums. Artwork is artwork, period. Even if it’s still inside your head! I feel it already exists as an entity at that point.

The Fields series was intended as a tribute to the intangible, so for the artworks to be binary code made sense to me. By binary code, I mean that the artworks are native to the digital realm. They are essentially ethereal data files that sometimes manifest in more “solid” media, like printed perspex or canvas.

However, after giving much thought to this, I believe that painting or sculpture can be as intangible and ethereal as binary code. All solidity is just an illusion created by our senses. Some Fields artworks have been translated into material supports in order to be exhibited. I’ve printed some of them directly onto clear acrylic sheets, others onto Dibond aluminum or onto paper… it depends on the occasion. For the new paintings I’m making with different spray guns, I work with stretched canvas mainly but I’m also experimenting painting directly on acrylic sheets, wood and other materials.

Your work, for a while, has tended toward abstraction but most recently it’s taken on this almost magnified and dissolved quality, at least in your most recent paintings. What’s prompted this direction in your work?

I think that lately my paintings have been getting blurrier and in some way dissolving, together with my beliefs. The more that I’m researching and meditating on these matters of consciousness, perception, the idea of reality and such, the more I see that everything is just conjecture. I think it can be freeing to accept all this and to play with it. I feel like this stage I’m in at the moment for me is about “dissolution”… but maybe after it, comes a rebirth based on an evolved perception of all these ideas, like waves layering on top of one another.

How do you approach the use of color in your work?

I’ve studied the subject of color theory and have found it useful over the years. However I believe that working with color more freely while following your intuition can take you to more personal places. For me the most important thing about color is observing carefully your surroundings, training your eyes. I’m continuously blown away by unexpected color combinations in nature, or in random places like a stain or a chipped wall.

Are there artists (present or past) whose work you feel is in a kind of conversation with your own?

Not sure which conversations my work is part of at the moment, but I guess time will tell. Until now, I’ve tried not to get too close to the work of other artists not to be influenced too much by it and mirror them. I feel that we already have so many influences that we can’t avoid that I prefer trying not to feed the conscious ones, if I can. However, I love the journey into the unknown of Hilma af Klint, the mystical quality in James Turrell’s work, the reflections on Zen and spirituality by John Cage, the poetic use of technology that Olafur Eliasson does, the use of symbolism in Maya Deren’s work, the boundless avant-garde spirit at the Bauhaus, the visionary ideas of Buckminster Fuller…

You’ve noted that your work is invested in exploring perception. Can you tell me a little more about what this means to you?

From time to time I have what I call my “phenomenological crisis”… this puzzlement is the basis of my recent work. Neuroscience states that reality is a collective hallucination. Quantum physics keeps getting weirder and less tangible each day. I often wonder if we as humans really have the capacity to understand what’s really going on in life. Our perception is biased, our senses create “facts” based on conjectures of what they think they are perceiving. They are not objective and it frustrates me that we may never know what the reality is. However, reality is such a complex term, as a “black and white” reality will never exist… there will always be a very rich grayscale made up from the impressions of each observer. And what role does consciousness have in all this? Is it the main character in the movie? Is it the one that makes it all happen? Are we the ones creating the whole thing? Is this experience a simulation, as some quantum physics theories state? If so, a simulation of what? Who designed it? Why?

I could go on for ages, but the only thing I know in the end is that I don’t really know. The more that I investigate, think and discuss about the subjects of perception and/or consciousness, the more that I’m perplexed by them – but in a good way! All this mystery and intrigue captivates me.

What do you keep around your studio or home for inspiration?

Since my move to Mexico, I’ve tried not to hoard as many things as I had when I lived in London or Barcelona, so my approach is quite minimalistic and functional. I feel that what inspires me the most is my garden, I see it from each of the rooms in the house, and I often work outside. I never get bored of admiring the changes of the seasons in the mountains or learning about the wildlife and greenery from this environment. I also love and have a lot of books, I’m addicted to information and I’m always reading about the most diverse subjects.

What are you currently working on?

I’m working on many new pieces at the moment. Researching, trying new techniques, producing at a larger scale. Soon I’ll be part of a couple of group shows, and in early November I’ll have a show in collaboration with Sol Oosel at the outdoor gallery josegarcia,mx has in Merida, Mexico (I’m really enjoying the challenge to produce work for open spaces!). Early next year, I’ll be having a solo show at josegarcia,mx’s main gallery in Mexico City, and at the same time I will also have a few pieces on display at Peana Projects’ booth during the Zona Maco art fair in Mexico City. Come and visit during art week, it’s always a lot of fun!

I think that lately my paintings have been getting blurrier and in some way dissolving, together with my beliefs. The more that I’m researching and meditating on these matters of consciousness, perception, the idea of reality and such, the more I see that everything is just conjecture. I think it can be freeing to accept all this and to play with it. I feel like this stage I’m in at the moment for me is about “dissolution”… but maybe after it, comes a rebirth based on an evolved perception of all these ideas, like waves layering on top of one another.

How do you approach the use of color in your work?

I’ve studied the subject of color theory and have found it useful over the years. However I believe that working with color more freely while following your intuition can take you to more personal places. For me the most important thing about color is observing carefully your surroundings, training your eyes. I’m continuously blown away by unexpected color combinations in nature, or in random places like a stain or a chipped wall.

Are there artists (present or past) whose work you feel is in a kind of conversation with your own?

Not sure which conversations my work is part of at the moment, but I guess time will tell. Until now, I’ve tried not to get too close to the work of other artists not to be influenced too much by it and mirror them. I feel that we already have so many influences that we can’t avoid that I prefer trying not to feed the conscious ones, if I can. However, I love the journey into the unknown of Hilma af Klint, the mystical quality in James Turrell’s work, the reflections on Zen and spirituality by John Cage, the poetic use of technology that Olafur Eliasson does, the use of symbolism in Maya Deren’s work, the boundless avant-garde spirit at the Bauhaus, the visionary ideas of Buckminster Fuller…

You’ve noted that your work is invested in exploring perception. Can you tell me a little more about what this means to you?

From time to time I have what I call my “phenomenological crisis”… this puzzlement is the basis of my recent work. Neuroscience states that reality is a collective hallucination. Quantum physics keeps getting weirder and less tangible each day. I often wonder if we as humans really have the capacity to understand what’s really going on in life. Our perception is biased, our senses create “facts” based on conjectures of what they think they are perceiving. They are not objective and it frustrates me that we may never know what the reality is. However, reality is such a complex term, as a “black and white” reality will never exist… there will always be a very rich grayscale made up from the impressions of each observer. And what role does consciousness have in all this? Is it the main character in the movie? Is it the one that makes it all happen? Are we the ones creating the whole thing? Is this experience a simulation, as some quantum physics theories state? If so, a simulation of what? Who designed it? Why?

I could go on for ages, but the only thing I know in the end is that I don’t really know. The more that I investigate, think and discuss about the subjects of perception and/or consciousness, the more that I’m perplexed by them – but in a good way! All this mystery and intrigue captivates me.

What do you keep around your studio or home for inspiration?

Since my move to Mexico, I’ve tried not to hoard as many things as I had when I lived in London or Barcelona, so my approach is quite minimalistic and functional. I feel that what inspires me the most is my garden, I see it from each of the rooms in the house, and I often work outside. I never get bored of admiring the changes of the seasons in the mountains or learning about the wildlife and greenery from this environment. I also love and have a lot of books, I’m addicted to information and I’m always reading about the most diverse subjects.

What are you currently working on?

I’m working on many new pieces at the moment. Researching, trying new techniques, producing at a larger scale. Soon I’ll be part of a couple of group shows, and in early November I’ll have a show in collaboration with Sol Oosel at the outdoor gallery josegarcia,mx has in Merida, Mexico (I’m really enjoying the challenge to produce work for open spaces!). Early next year, I’ll be having a solo show at josegarcia,mx’s main gallery in Mexico City, and at the same time I will also have a few pieces on display at Peana Projects’ booth during the Zona Maco art fair in Mexico City. Come and visit during art week, it’s always a lot of fun!

That which is looked upon by one generation as the apex of human knowledge is often considered an absurdity in the next, and what is regarded as a superstition in one century, may form the basis of science for the following one.

Paracelsus (1493-1541)

Off-White

a text by Enrique Giner de los Ríos for the Fields at Amós Salvador exhibition catalogue

Spanish version here * lee aquí la versión original de este texto

Color is the mother tongue of the unconscious mind.

Carl Gustav Jung

The sea is dark like wine, just like sheep and oxen, the sky is bronze colored , clouds are purple, and green are nightingales and honey (always according to The Iliad and The Odyssey). Homer, besides being witty, lived in a Greece with a limited palette of colors, at least as far as vocabulary is concerned. Empédocles, presocratic philosopher and great theorist of color, had established an order in which tonalities were divided into four large groups: white, black, red and yellow (and what derived therefrom). There was no blue in Ancient Greece.

William Gladstone, in the nineteenth century, was the first to notice the strange analogies Homer used to describe the color of things. Gladstone, in addition to being prime minister of Great Britain in four occasions, published an important book tittled Studies on Homer and the Homeric Age, where a careful study about the use of the color in the works of the Greek poet is made. In it, he concludes that the Greeks saw only in black and white, with small touches of red. They had not physically developed the ability to see colors. This cruel theory had some resonance in the Victorian period due to of the importance of the author and the affluence in his explanation. Fortunately, over time it was found that Homer was not color blind or his people suffered any kind of visual atrophy. They were able to see the same colors as us even if they named or related them to different things. The names of a color often described texture, temperature or light. Far from being conceived as a mere surface, color evoked sensations and was related to certain spirituality.

Other civilizations of the time also witnessed green dawns, horses with violet mane like rainbows or apples, silver lakes and other chromatic aberrations that I envy deeply. The scarcity of names was common among them, as was the logic with which they arose. This was declared by the German philosopher Lazarus Geiger, inspired by the work of Gladstone. The same tones are repeated in almost all cultures practically in the same order of appearance: first the black and white (light and dark), then the red (blood and easy to produce dyes), and finally yellow and green (the colors of vegetation). Thinking of blue was a luxury. The blue of the sky was thus conceived only by the Egyptians, who had a great mastery of color and chemistry, which led them to create a blue pigment considered the first synthetic dye in history.

When a color doesn’t have a name it doesn’t exist. The designation of a color and the perception we have of it are not necessarily linked, but having names helps us to define a spectrum. It also restricts us and subjects us to an imposed order, to a convention. Sensitive observation, poetry, altered states of consciousness, and Homer's comparisons may perhaps save us from this yoke. Freed us every so often from norms that uniform our perception, that mutilate the imagination of children who color blue clouds on *bond* white skies, timidly inverting the order to save paint and time.

The world is governed by great abstractions, we understand space in three dimensions thanks to Euclid. Once we learn to see space as a composition of two-dimensional planes generated by an infinite succession of lines created by points without any dimension, there is no turning back. It will be very difficult to interact with space intuitively ever again. Euclidean geometry helps us understand something that does not exist, while denying other perceptual realities. Sometimes conventions work as social norms, they help us interacting as individuals in society, but they prevent us from wearing white shoes in the autumn, running with scissors, disguising ourselves as an animal to go to the cinema on Monday, or eating a mango with our hands.

The chromatic spectrum has grown along with its names. In the 20th century we learned the unmistakable shimmering tones of Kodachrome, the famous film for slides created by Kodak in the 1930s; In the 60's Pantone was invented, the main color identification system that year after year tries to impose a new trend tonality with an absurd name. Four years ago we met the Vantablack, the blackest black, capable of absorbing up to 99.9% of the light, making any object painted with this pigment look like a dark hole in space; and we had never seen as many pink hues as in this decade, or so many old and new names fighting to be the ultimate tone (champagne pink, rose pink, salmon pink, COS pink…). Blue has long been the favorite color among the majorities and the amount of tonalities is overwhelming. Indigo is artificially produced in vast quantities, and is one of the most harmful water contaminants.

Ana Montiel's relationship with color oscillates between absolute erudition and primitivism, between the complex and the simple. The relationship is as childish as well-educated, with precepts of a man of science, of a witch, of make believe, or none of the above. Ana knows perfectly the principles of the subtractive and additive synthesis of color, recites from memory fashionable tones in the world and her changing selection of personal favorites, she dresses in different shades of black, creates her own pigments using ancestral techniques, grinding chalk or using new materials, a slightly different yellow than what you expected can ruin your day, know the ideal combination to print a deep black in CMYK, and most likely calibrate the screen of your computer. I would never discuss whether a photograph was taken at Kodachrome, Fujichrome or Ektachrome, and much less about the vagueness of a car's color. Biotechnology is one of the last obsessions of the artist, is waiting for a chlorophyll droplets that allow temporary night vision and what is necessary to become a tetrachromatic human, with four different types of cone cell in the retina making it able to distinguish, among other things, up to 10 tones in the rainbow.

Her perception of the chromatic spectrum is not restricted by names and conventions. Ana does not perceive color as a solid surface, she associates without any prejudices all the different tones and gradients to sensations or moments, to emotions, or to objects without a name. Layers of hues run through her canvases like white noise, emerging from the depths to disappear again, generating different narratives for each viewer. One can spend hours standing in front of one of her Fields, waiting for the cloud of color that created all that frenzy a few minutes ago to happen again, in the same way you wait at a large aquarium for the mother walrus and her babies to swim again in front of you while they greet you.

Ana's intuition about the use of color is influenced by the writings of Josef Albers, by psychology, by science and its advances, by Derek Jarman's essays, by esoteric readings, by what she hears on the street, by her obsession with synesthesia, altered states of consciousness, the aurora and the harsh midday light in her house in Tepoztlan. The sea and the sheep are dark like wine if she so wishes. And the sunsets are off-white.

Enrique Giner de los Rios

An extract from “Waking, Dreaming, Being: Self and Consciousness in Neuroscience, Meditation and Philosophy”

A book by Evan Thompson

![]()

What exactly is consciousness? The oldest answer to this question comes from India, almost three thousand years ago.

Long before Socrates interrogated his fellow Athenians and Plato wrote his Dialogues, a great debate is said to have taken place in the land of Videha in what is now northeastern India. Staged before the throne of the learned and mighty King Janaka, the debate pitted the great sage Yājñavalkya against the other renowned Brahmins of the kingdom. The king set the prize at a thousand cows with ten gold pieces attached to each one’s horns, and he declared that whoever was the most learned would win the animals. Apparently Yājñavalkya’s sagacity did not entail modesty, for while all the other priests kept silent, not daring to step forward, Yājñavalkya called out to his student to take possession of the cows. Challenged by eight great Brahmins, one by one, Yājñavalkya demonstrated his superior knowledge. As a favor to the king, he allowed him to ask any question he wanted. In the ensuing dialogue, told in the “Great Forest Teaching” (Bṛhadāraṇyaka Upaniṣad)—a text dating from the seventh century B.C.E. and the oldest of the ancient Indian scriptures called the Upanishads—Yājñavalkya gave the first recorded account of the nature of consciousness and its main modes or states.

The dialogue begins with the king, knowing exactly where he wants to lead the sage, asking a simple question: “What light does a person have?” Or, as it can also be translated: “What is the source of light for a person here?”“The sun,” replies the sage. “By the light of the sun, a person sits, goes about, does his work, and returns.”“And when the sun sets,” asks the king, “then what light does he have?”“He has the moon as his light,” comes the reply.“And when the sun has set and the moon has set, then what light does a person have?”“Fire,” answers the sage.

Persisting, the king asks what light a person has when the fire goes out, and he gets in reply the clever answer, “Speech.” Yājñavalkya explains: “Even when one cannot see one’s own hand, when speech is uttered, one goes toward it.” In pitch-black darkness, a voice can light your way.

The king, however, still isn’t satisfied and demands to know what light there is when speech has fallen silent. In the absence of sun, moon, fire, and speech, what source of light does a person have?

“The self (ātman),” Yājñavalkya answers. “It is by the light of the self that he sits, goes about, does his work, and returns.”This answer makes plain that the dialogue has been moving backward, from the distant, outer, and visible to the close, inner, and invisible. Nothing is brighter than the sun, or the moon at night, but they reside far away, at an unbridgeable distance. Fire lies closer to hand; it can be tended and cultivated. Speech, however, is produced by the mind. Darkness can’t negate the peculiar luminosity of language, the power of words to light up things and to close the distance between you and another. Yet speech is still external in its being as physical sound. The sun, moon, fire, and speech—we know each one by means of outer perception. The self, however, can’t be known through outer perception, because it resides at the source of perception. It isn’t the perceived, but that which lies behind the perceiving. The self dwells closest, at the maximum point of nearness. It’s never there, but always here. How could we possibly find our way around without it? How could outer sources of light reveal anything to us, if they weren’t themselves lit up by the self? And yet, precisely because the self is so intimate, it seems impossible to have any clear view of it and to know what it is.

Finally, the king is able to ask the question he has all along been aiming toward: “What is the self?”Yājñavalkya answers that the self (ātman) is the inner light that is the person (puruṣa). This light, which consists of knowledge, resides within the heart, surrounded by the vital breath. In the waking state, the person travels this world; in sleep, the person goes beyond this world. The person is his own light and is self-luminous.As this answer unfolds, it becomes clear that the “light” Yājñavalkya is talking about is what we would call “consciousness.”

Consciousness is like a light; it illuminates or reveals things so they can be known. In the waking state, consciousness illuminates the outer world; in dreams, it illuminates the dream world.It’s here, in Yājñavalkya’s answer to the king’s question about the self, that we find the first map of consciousness in written history.

Yājñavalkya explains to the king that a person has two dwellings—this world and the world beyond. Between them lies the borderland of dreams where the two worlds meet. When we rest in the intermediate state of dreams, we see both worlds. The dream state serves as an entryway to the other world, and as we move through it we see both bad things and joyful things.

In the waking state, we see the outer world lit up by the sun. Yet we also see things when we dream. Where do they come from, and what makes them visible? What is the source of the light illuminating things in the dream state?

Yājñavalkya explains that in the dream state we take materials from the entire world—this world and the other one—break them down, and put them back together again. Although the dream state lies between the two worlds, it’s a state of our own making. The person creates everything for himself in dreams and illuminates it all with his own radiance:When he falls asleep, he takes with him the material of this all-containing world, himself breaks it up, himself re-makes it. He sleeps by his own radiance, his own light. Here the person becomes lit by his own light.

What exactly is consciousness? The oldest answer to this question comes from India, almost three thousand years ago.

Long before Socrates interrogated his fellow Athenians and Plato wrote his Dialogues, a great debate is said to have taken place in the land of Videha in what is now northeastern India. Staged before the throne of the learned and mighty King Janaka, the debate pitted the great sage Yājñavalkya against the other renowned Brahmins of the kingdom. The king set the prize at a thousand cows with ten gold pieces attached to each one’s horns, and he declared that whoever was the most learned would win the animals. Apparently Yājñavalkya’s sagacity did not entail modesty, for while all the other priests kept silent, not daring to step forward, Yājñavalkya called out to his student to take possession of the cows. Challenged by eight great Brahmins, one by one, Yājñavalkya demonstrated his superior knowledge. As a favor to the king, he allowed him to ask any question he wanted. In the ensuing dialogue, told in the “Great Forest Teaching” (Bṛhadāraṇyaka Upaniṣad)—a text dating from the seventh century B.C.E. and the oldest of the ancient Indian scriptures called the Upanishads—Yājñavalkya gave the first recorded account of the nature of consciousness and its main modes or states.

The dialogue begins with the king, knowing exactly where he wants to lead the sage, asking a simple question: “What light does a person have?” Or, as it can also be translated: “What is the source of light for a person here?”“The sun,” replies the sage. “By the light of the sun, a person sits, goes about, does his work, and returns.”“And when the sun sets,” asks the king, “then what light does he have?”“He has the moon as his light,” comes the reply.“And when the sun has set and the moon has set, then what light does a person have?”“Fire,” answers the sage.

Persisting, the king asks what light a person has when the fire goes out, and he gets in reply the clever answer, “Speech.” Yājñavalkya explains: “Even when one cannot see one’s own hand, when speech is uttered, one goes toward it.” In pitch-black darkness, a voice can light your way.

The king, however, still isn’t satisfied and demands to know what light there is when speech has fallen silent. In the absence of sun, moon, fire, and speech, what source of light does a person have?

“The self (ātman),” Yājñavalkya answers. “It is by the light of the self that he sits, goes about, does his work, and returns.”This answer makes plain that the dialogue has been moving backward, from the distant, outer, and visible to the close, inner, and invisible. Nothing is brighter than the sun, or the moon at night, but they reside far away, at an unbridgeable distance. Fire lies closer to hand; it can be tended and cultivated. Speech, however, is produced by the mind. Darkness can’t negate the peculiar luminosity of language, the power of words to light up things and to close the distance between you and another. Yet speech is still external in its being as physical sound. The sun, moon, fire, and speech—we know each one by means of outer perception. The self, however, can’t be known through outer perception, because it resides at the source of perception. It isn’t the perceived, but that which lies behind the perceiving. The self dwells closest, at the maximum point of nearness. It’s never there, but always here. How could we possibly find our way around without it? How could outer sources of light reveal anything to us, if they weren’t themselves lit up by the self? And yet, precisely because the self is so intimate, it seems impossible to have any clear view of it and to know what it is.

Finally, the king is able to ask the question he has all along been aiming toward: “What is the self?”Yājñavalkya answers that the self (ātman) is the inner light that is the person (puruṣa). This light, which consists of knowledge, resides within the heart, surrounded by the vital breath. In the waking state, the person travels this world; in sleep, the person goes beyond this world. The person is his own light and is self-luminous.As this answer unfolds, it becomes clear that the “light” Yājñavalkya is talking about is what we would call “consciousness.”

Consciousness is like a light; it illuminates or reveals things so they can be known. In the waking state, consciousness illuminates the outer world; in dreams, it illuminates the dream world.It’s here, in Yājñavalkya’s answer to the king’s question about the self, that we find the first map of consciousness in written history.

Yājñavalkya explains to the king that a person has two dwellings—this world and the world beyond. Between them lies the borderland of dreams where the two worlds meet. When we rest in the intermediate state of dreams, we see both worlds. The dream state serves as an entryway to the other world, and as we move through it we see both bad things and joyful things.

In the waking state, we see the outer world lit up by the sun. Yet we also see things when we dream. Where do they come from, and what makes them visible? What is the source of the light illuminating things in the dream state?

Yājñavalkya explains that in the dream state we take materials from the entire world—this world and the other one—break them down, and put them back together again. Although the dream state lies between the two worlds, it’s a state of our own making. The person creates everything for himself in dreams and illuminates it all with his own radiance:When he falls asleep, he takes with him the material of this all-containing world, himself breaks it up, himself re-makes it. He sleeps by his own radiance, his own light. Here the person becomes lit by his own light.

A TRIBUTE TO THE

NON-MATERIAL

(from the Fields at Amós Salvador exhibition catalog)

Nikola Tesla said that whenever science begins to study non-physical phenomena it will progress in a decade more than in all previous centuries.

I often have the recurring feeling that we humans miss out on many things by perceiving and measuring everything in such a materialistic way (quantifying and testing as was done in ancient past). Some branches of modern science have been trying to dismantle the monopoly of such materialistic practices for decades, with ideas that state that the reality we perceive is a mere collective hallucination and that what we understand as matter is not really solid but just energy in motion. Solidity is an illusion, but since our senses are so "hyper-realistic", the perception we have of our environment through them is manifested in a way that makes us feel it as undoubtedly solid.

Richard Feynman (Nobel Prize in Physics, 1965) believed that it is much more interesting to live admitting that we do not know, than to live believing we have answers that could be incorrect. He admitted having approximate answers, possible beliefs and different degrees of uncertainty about a variety of issues, but he was not completely sure of anything. He was not afraid of not knowing things, of feeling lost in a mysterious universe of which he did not know its purpose; you could say he was comfortable in uncertainty. Even though I may not be as comfortable with the perplexity of the universe as Feynmann was, often, the search for the unknown causes me to find myself wrapped in a feeling of ecstasy and a sense of adventure so stimulating that they make me recognize them as the engines that keep me moving. To dream with colors that I’ve never met, to learn about all the possible disciplines or to try and translate ideas or perceptions that flirt with the ineffable to an artistic work; everything is an excuse to learn and find meaning. I feel that the road is the most important thing, the process. The works work as witnesses of this research expedition.

THE DICTATORSHIP OF THE SENSES

Why does something have more credibility if we see or touch it than when we feel it? And what about the number of times we thought we saw something that in the end was not there, or heard something that was impossible? Why is it that we give so much credibility to our five senses, when neuroscience tells us again and again that what we perceive are pure conjectures and impressions of the most subjective? Whenever we are perceiving, in reality what we are doing is creating (we influence the result in an active way with our cognitive process). Would it help to alleviate this dissonance if we expanded the categorization of our senses by adding an additional pair based on feeling and intuition? I think it would be similar to when our language evolves and expands to express ourselves in a richer and more precise way.

What is it that makes us believe in some things and not in others? Would you deny the existence of love due to its imprecise nature and how difficult it is to carry out a measurement of it? Isn’t it a little hypocrite from our part that emotions are considered subjective but the senses with which we perceive are not? Does it makes us restless to realize nothing is physical, and everything is just an energy network? Sometimes, when I reflect on these issues, I get a knot in my stomach and feel a bit of vertigo, the abyss of infinite possibilities that I begin to ponder is overwhelming and exciting in equal parts.

There is a multiverse theory that states that this reality that we experience is a mere virtual simulation. Simulation? Is the squirrel that I see climbing up the guava tree in the garden a mirage? Science says that the squirrel, the guava, and myself are simulations. None of us are material and we are only expressions of energy in motion, comparable to the one we can live with a next-generation video game in which one uses one of those virtual reality caps. This theory is just as farfetched as any we can have about the reality we experience. Reflecting calmly, everything is just as speculative as mysterious when one is inquiring into the nature of this experience that we live. All illusions, from the magical chiaroscuro of a full moon night in the desert, to the avocado-taco that I am about to eat, I am co-creating everything I perceive.

Fields is a tribute to the intangible, a personal respite in the dictatorship of this illusory material world. A reflection about what possibly exists even if I am not aware. I feel it's like reaching out for something or someone you probably never get to know. Fields is an exercise in faith disguised as a chromatic adventure.

For me, the idea of security is almost as elusive as the idea of solidity. What seems immovable one day, the next will be just a memory. Life communicated this to me loud and clear during my teenage years with the illness and passing of my late mother. What seemed the most stable pillar in my life, threatened with becoming history. After the shock, the denial, the crisis and the all the crying, the pseudo-zen reaction that I managed to take, to get on with life, was a carpe diem attitude with which I embraced every day as if it were the last. Squeezing possibilities and experiences as much as possible.

Today, despite missing this wonderful being every day, the feeling of gratitude I have for her and the situation is much greater than the sadness. So much to thank my mother today and always, so much to thank life! The learning and growth that such an experience grants is priceless.

Attachment brings sadness. If we had been educated with a different approach, one based on detachment and the acknowledgement of impermanence, I feel that we could be handling better the ups and downs of life. Enjoying things while they are there, without clinging, with a spirit of profound awe and gratitude regarding the mystery of existence.

The feeling of stability is highly seductive, I consider it similar to that of solidity. Both sell you an idea of security that we all crave and they are like two faces of the same mirage, intangible and powerful.

UNCERTAINTY AS A KEY TO EVERYTHING

Denying something deprives us to understand it, but doubting it opens us to questioning it, reflecting it and maybe even deciphering it. Our daily life is still ruled by the materialistic practices of Isaac Newton’s era. Attentive to the mechanical and quantitative, focused on the subject (what we see and can measure). Any glimmer of certainty of Newton's proposal was brought down with the advent of quantum physics in modern science. Why do we not incorporate the vagueness of the latter into our daily life? I think being comfortable in uncertainty is about the most powerful gifts we can make ourselves as a species. Not classifying and quantifying ideas or situations constantly, but living with them with respect and curiosity, wanting to understand but accepting that there will always be much more that one will not understand.

Carl Sagan said that we give meaning to our world with the courage of the questions we ask and with the depth of our answers. I feel that questioning our structures and not taking things for granted is imperative for our existence. To be able to slander certainty and embrace a nebula of questions with an inquisitive mind and an almost puerile enthusiasm. To engage in a conversation with doubt to see it become an ocean of possibilities, while our spirits dance lightly as they are counseled by the pattern of non-solidity.

Uncertainty as a possibility, and us being able to transcend the canons of what we currently consider reality, embracing the unknown and becoming one with it.

Ana Montiel, 2018

UNA

ENTREVISTA

Y

UN

MIXTAPE

PARA LOCAL.MX

(para los monógamos de Spotify, aquí está el playlist en vuestra plataforma favorita)

Chromatic Rhapsody

(random musings about the history, science and mysticsm of color)

The history of humanity could easily be told through color. Rudimentary pigments made out of charred bones, green tones that would turn people insane and are suspected of making ill Napoleon hiself, fluorescent hues made to be used and abused at rave parties… color is always there, anywhere you look.

No blue pigment had been discovered for more than 200 years (since the birth of what we know as cobalt blue), until recently when out of the blue—pardon the silly pun— YInMn was discovered at the University of Oregon.

Crayola has organized a contest to choose a name for this new tone in order to include it at their crayon sets. What a tremendous responsibility to name a new color. So many possibilities!

From the red hues used in cave paintings, made out of grinded mineral pigments like iron oxide or hematite, to the recent red iPhone; as Josef Albers said, if one says 'red' and there are fifty people listening, it can be expected that there will be fifty reds in their minds. And one can be sure that all these reds will be very different.

“Some painters transform the sun into a yellow spot, others transform a yellow spot into the sun” — Pablo Picasso